In her article ‘The Fading Art’, published in November’s Now Then, Anna Pintus approached “the conflict between nostalgia and progression” in cinema. She began and ended on the point that, ultimately, “personal opinion rules”. But Pintus is uncompromising in the body of her article that the soul of cinema belongs to traditional film, and will probably fade away with it.

“Film as an art is now clouded with innovation,” she writes. She is clear and literal here, writing without jargon, but in doing so she exposes the absurdity behind her argument. How can anything be “clouded with innovation,” a word that is synonymous with clearing the fog?

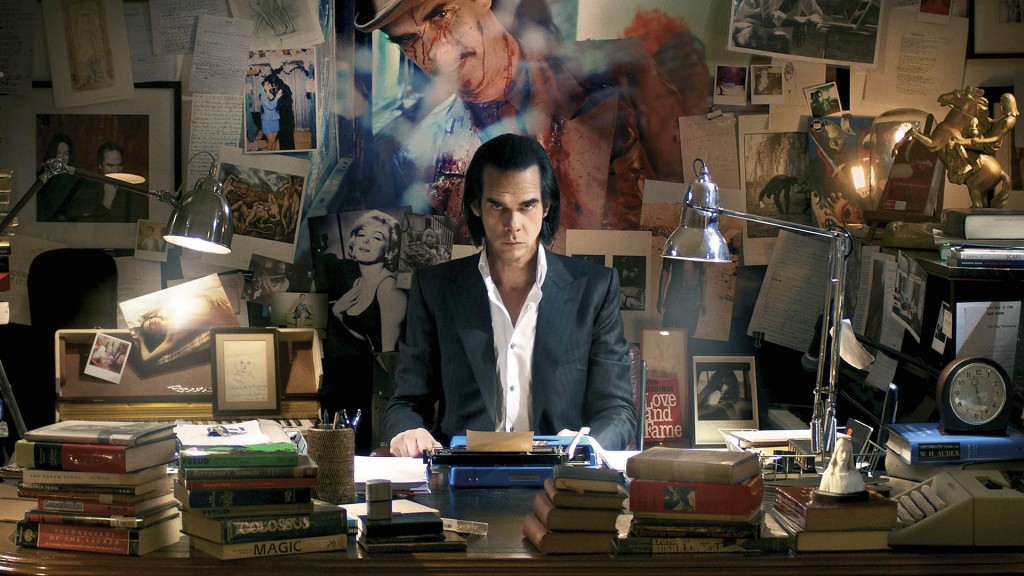

The aid that digital and social media has granted to collaborators in art has produced films like Kiss The Water and 20,000 Days on Earth, which feature a blend of animation, photography and a traditional documentary style. The crowd that has embraced digital innovation are the up-and-comers who will replace the old guard. Anyone who watched either of these films will trust that they are just as passionate about film’s tradition and they are ready to take on the old and new. No film managed to pack out the Showroom last autumn like 20,000 Days on Earth. It was not only a powerful film, but a nationwide interactive event, and a great example of what one can see more and more – digital innovation exposing a wider audience to art cinema.

That is exciting and new. Of course, Pintus is right in saying that the ‘remastering’ of old classics has become obsessive. If one wishes to screen, for example, an early Ingmar Bergman film on a large screen, then what the audience sees should be as close to what Bergman wanted as possible. Re-formatting and remastering should only go as far as making a film viable for digital projection. But as the argument against re-formatting is an argument for the artist’s autonomy, the argument against digital innovation and the “perfection in today’s digitally restored era” is an argument against that same autonomy. One should have the option of using old film and Christopher Nolan deserves all his praises for championing the cause that led to studios stockpiling old Kodak film. Nevertheless, filmmakers are due the autonomy that digital film offers.

João Paulo Simões mounted a similar argument to Pintus the following month in his article ‘Tactile Thought’. Whereas Pintus praises Nolan and Tarantino for their use of film, Simões laments “Martin Scorsese, Win Wenders [and] Jean Luc Godard” for purposing large projects around 3D projection. For him their capitulation is “a reflection of the era we’re living in”. But 3D has been tried before, failed, and will be tried again if it cannot establish itself now. If it survives it will be because the technology is worth keeping and not because we are now demanding more “immediate satisfaction” than we ever were. The long-term fortunes of 3D cinema are based in its practicality, not our psychology.

The overall sentiment of both these articles is that an art form has been corrupted by technological devices that have nothing to do with the art itself. The supposed affect of “instant gratification” technologies upon cinema is conjecture because streaming is still relatively new. One would do well to remember that cinema was begun by two brothers who thought their cinematographe “had no future”, had nothing to do with art and was a sort of toy.

Words: William Herbert.