A History of American Anxieties.

With Halloween right around the corner, I’ve found myself delving into the annals of horror cinema, and who greater to start with than the lord of the dead, Romero.

George A. Romero is widely considered as the leading pioneer of this genre, and rightly so. His Living Dead trilogy (the less said about the other films the better) paved the way for all modern zombie movies, inspiring remakes and parodies left, right, and centre. These films, the genesis of the genre, seem at first glance like cheap exercises in gore and violence. However, shallow, these films are not. After re-watching the original trilogy, it became clear to me that these films chronicle the anxieties of the American public throughout the 20th century, merely using the zombies, blood and guts as a visual medium to convey these allegories. Let’s talk about the first film of the trilogy, 1968’s Night of the Living Dead.

The film begins in a graveyard, where siblings Johnny and Barbara are visiting their father’s grave, and placing a wreath. Barbara, dead serious, and solemn throughout, doesn’t seem best pleased with Johnny’s ‘take it or leave it’ attitude. She commemorates her father respectfully, while Johnny just seems to want to get out of there as soon as possible. “Praying’s for church, huh?” Johnny says to Barbara as she kneels. “And there ain’t much sense in me going to church”, he retorts after she chastises his lack of appearance at church. This exchange perfectly sums up the overarching theme of the film: the fear of the death of religion and traditional values in America. Johnny, a modern man, teases Barbara as she becomes frightened of his lack of respect, and lack of conformity to ritual. He questions the entire experience at every point, and Barbara seems to become more nervous as time goes on.

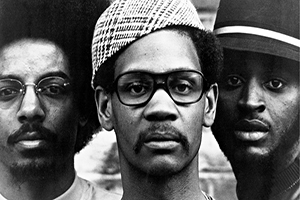

Johnny is eventually brutally murdered by a zombie, and Barbara retreats to a farmhouse, where the thematic elements become stronger and stronger. Ben, the main protagonist from here on in, is black. While no direct comment on this is made throughout the film, it is obvious that some characters may have a problem with this. Judy seems terrified of Ben, often becoming hysterical, and at other times as quiet as a mouse, as if he could lash out at her at any point. Harry seems to have a problem with Ben, as their egos, and contradicting ideologies clash. Harry wants to hide in the basement, wait it all out, and have faith in the American authorities to save them. Ben, however, wants to stay upstairs, fight, and have the chance to escape should the authorities fail (the source of his ultimate demise). Harry eventually becomes tired of Ben’s position of power, and whether racially motivated or not, tries to usurp him and steal his gun. Ben takes the gun back, and ends up killing Harry. This exchange again symbolises the death of American values, and more importantly, the fear of change (Ben) felt by the average, middle-class American (Harry).

Considering the time the film was made, and the general social context of that time, these ideas might not be as implausible as you might think. At the end of the 60s, a decade of social turbulence (contrary to the popular image of ‘free love’), things in America were changing. People were starting to distrust authority, evidenced by the failure of the authority in NOTLD to help any of the survivors in the farmhouse. There were rapid technological advances such as the moon landing, reflected in the prominence of the downed probe in the film. There were fractures within the counterculture movement, shown through the fractures that appear in a house full of people with the same goal: survive.

So, next time you sit down to enjoy an all out gore-fest, consider the meaning behind it. It may seems like 2 hours of pure bloodshed, but there might be something deeper for you to ponder.

Words: Bill Herbert.